This is something I’ve been meaning to do for years, it happened often enough in the medieval period, to cooking pots and also some buckles and the like, basically anything which would look nicer with a shiny corrosion resistant surface. I tinned iron nails many years ago, but somehow never got around to trying it on copper or bronze. It is a sensible thing to do to a cooking vessel, to ensure it doesn’t taint the food you are cooking.

So, this is how you do it, according to Biringuccio (Page 369 of the paperback Dover edition):

“To do this, a little salt and vinegar is boiled and the vessels are cleaned well inside with this. Then some tin mixed with a fourth part of lead and with some powdered Grecian pitch is melted. The tin is applied as you wish by rubbing it all over the outside and inside with a brush of tow tied to the point of a tool or held with a pair of tongs.”

I’ll skip using the lead for obvious reasons. And I don’t have any tow, which presumably would be made from flax or hemp rope. The pitch acts as a flux, helping prevent oxidation of the liquid tin and lead. I have other substances which might do, such as lard or beeswax.

In order to tin the group cauldron therefore, I set it up like this on a fire:#

It took a while to heat through due to the mass of bronze.

I put some beeswax in it and some pure tin used for soldering. Eventually this melted:

Now came the interesting thing. No matter how I scraped the tin around the inside using a piece of leather, it didn’t stick properly to the bronze. Which wasn’t too surprising, but it is nice to demonstrate clearly how the plain straightforward instructions are lacking something.

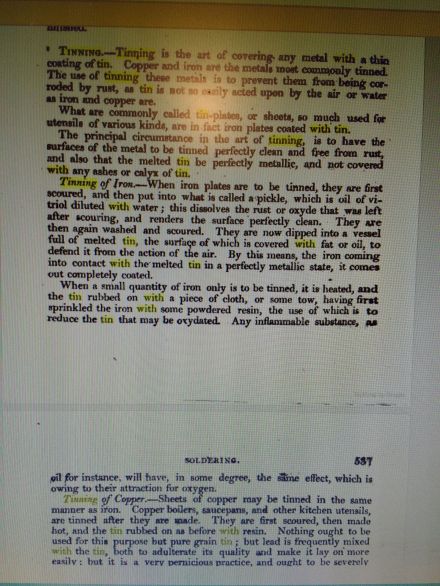

Amazingly, this lack of information persisted even into the 19th century. This photo is of a book found on google books, and it is remarkably similar to the instructions given by Biringuccio:

After doing it a second time I had the following result:

Not tinned properly at all.

This gave me a good clue what was wrong – the metal was so hot the tin melted off it again, and what I needed to do was to control the heat. So searching the internet for more information, I found this article, in which a man who re-tins old pans and such explained the importance of the temperature, which is ideally kept at to ten degrees above the melting point of tin.

http://www.marthastewart.com/268808/retinning-copper-pans

Thus the limits of Biringuccio. Over time I expect to find more about such limits, since leaving out the importance of limiting the temperature of the item being tinned is rather a big thing.

Now I just need to decide whether to try it again in various ways, such as using a ladle full of tin and a blowtorch, or else use an electrolytic method and tin in solution.

You might think that I go about these things in an inefficient and ineffective manner, but actually I find I learn best through making mistakes, and in making the mistakes, I get a much better idea of the parameters involved in the process and what skills are involved. Plus by following the recipe as nearly as possible as given, it makes clear how good it is.

I thought tinning bronze/copper cookware was a post-medieval thing?

Also, when did you cast a bronze cauldron, and where’s the writeup? I’d love to compare notes.

LikeLike

Biringuccio ha instructions for it, so in that respect it is post-medieval, but I think I have come across mention of it somewhere in medieval times. They did like to tin a lot of things for purposes of rust resistance and looking nice and shiny.

I’m not so sure about cauldrons specifically, but I would beware making broad statements on the basis of the handful of medieval cauldrons that have survived to this day.

I haven’t cast a bronze cauldron yet, that’s something I want to do in the future. Instead this one came from Historic Castings, who are still in operation. I can send you their email if you like. It is a leaded alloy though, which is another reason I am tinning it.

LikeLike

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #36 | Whewell's Ghost

Hey Guthrie,

I watched a tinsmith working in Turkey some years back, and he was using an oven pretty close to a tandoor in form to tin copper and brass in. so very diffuse, rather than direct, heat.

LikeLiked by 1 person